Jolting along the road between Gonbad-é Qabus and Gorgon, the scenery is marvellous. The flanks of the eastern end of the Alborz Mountains step down in a green avalanche to the fertile plains, growing rice, vegetables and fruit. The tops of the mountains are invisible in the grey overcast which has, at intervals, brought a light drizzly rain to the steppe. From the forested valleys, wreaths of mist rise up from the thick, verdant jungle.

The land is extraordinarily fertile and fecund. The crops are healthy, the animals well fed, apart from the occasional donkey. Donkeys always seem to look unhappy. Perhaps it’s because they’re always being ridden, and they always seem to wear an expression that says, “don’t tell me about life.”

This morning we were tossed out of the Hotel-é Kahyyam. We didn’t know if it was full for tonight, or if they were just sick of us. But whatever the reason, we were told to leave. Out on the streets of Gorgan, we sought accommodation at another hotel but were told we would have to pay thirty-three dollars for a night. We politely refused. Seeking to find another place, we were befriended by a taxi driver, who took us to his house for breakfast.

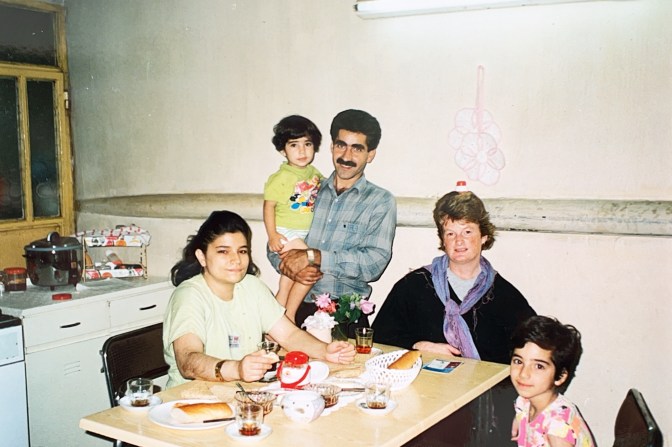

With his wife and two daughters, one of whom was called Roxana, we ate fresh bread, with butter and jam, and drank chai, while holding a very limited conversation. The taxi driver was adamant that we should stay the night at their house, and tomorrow we would all go on a picnic. We insisted politely, however, that tomorrow we had to go to Tehran for our visas (which is true) and that today we would visit the Gonbad-é Qabus.

Our tame taxi driver drops us at a bus terminal where we board a bus for Gonbad-é Qabus. The trip takes one and a half hours, and it rains intermittently as we travel across the plain. The leaves of the maple and poplar trees alongside the road begin to turn as the season changes from summer to autumn.

Passing through a nondescript town, the overcast begins to break up. Sunlight penetrates the clouds, immediately warming the air which becomes steamy and humid. The jungle looks even darker in the sunlight, rolling away to the west in great green billows. Where it comes down to the roadside, picnic areas are crowded with cars, each vehicle having a cluster of picnickers next to it.

The patches of forest give way once again to farmland — tea and oranges — brick kilns, and graceful slender Lombardy poplars. Great chunks of blue sky appear amid the ragged shred of the overcast, and the effect known to artists as Linear Perspective gives depth and distance to the forest-clad ranges.

Beyond Gorgon, we pass beneath the hill upon which stands the array of aerials and communication dishes. Along the road, a pageant of life is played out. Groups of sheep stand in huddles, their heads together for shade. Vendors sit next to huge piles of melons. Through a crumbling mud-brick gateway can be seen the remains of two steam rollers, rusting amid weeds and scrawny bushes. A tree outside a paint shop is foliated not with leaves, but empty paint tins. A painted sign next to Khomeini’s scowling effigy proclaims, “DOWN WITH AMERICA!”

The mountains are hidden in shadow and shade, but the plains are sunny and shimmering. The roadside continues to be an impromptu picnic spot for hundreds of holidaymakers, cooking their lunch in the shade of maples, eucalypts, and conifers.

The Turkoman town of Gonbad-é Qabus is flat and uninspiring, although the markets look quite interesting, with a wide range of colourful goods for sale. The people have the characteristic Central Asian look: dark spiky hair and sloping eyes with brown leathery skin.

From the minibus terminal, we take a taxi through town to the low hillock upon which stands the tower for which the town is named. Built in the tenth century as a monument and tomb for the poet Qabus (Full name: Abol-Hasan Qābū bin Wušmagīr bin Ziyar Sams al-ma’ālī), the imposing brick tower stands thirty-three metres tall and is capped with a conical roof of tiles upon which on the north side grows moss and small grassy plants.

The tower is visible from up to thirty kilometres away. We had seen it amid chimneys and pylons long before we reached the town. Close up, it is a strange and wonderful sight, at once beautiful in its design and construction, and stark with its background of dark clouds. The dank and empty interior of the tower, apparently locked when David St Vincent [the author of our Lonely Planet Iran guide] visited, is accessible through a barred door, and one can peer into the shadowy heights of the tower, where still hangs the chain, from which the coffin of Qabus was attached.

We spend half an hour at the tower, then catch a taxi to the bus station, where we have to wait for forty-five minutes before the next bus bound for Tehran departs. Passing through the town, en route to the bus station, I see George Michael on a motorcycle.

Driving out of Babel, we pass through an area of garages and steelmakers. The air of the place is grey and dirty and shabby, made more so by the mud left by the heavy rain which has lashed the coastal plains since Beshahar. We pass a car sales shop, its brightly painted sign advertising Mercedes and BMW. In the showroom, however, sits one lonely blue-painted second-hand Paykan.

At Amol, we turn south, heading into the mountains, which separate the lush, wet Caspian coast from the dry plains of central Iran. The road follows a narrow valley, its floor farmed with an intricate patchwork of rice paddies hemmed in by the steep sides of the valley, which is heavily forested. A river runs down the valley floor, its waters muddy from the recent rain. Where it has cut into the opposite bank, the thick layer of loess soil, blown down from the steppes over thousands of years, can be seen. It is this soil that provides such a fertile base for the forests to grow and for men to farm.

Further into the mountains, the valley closes in completely. The portals of the forest drop sheer to the valley floor. Jagged fingers of rock jut from the forest and vegetation clings to every nook and cranny. Within a few kilometres, the vegetation changes from thick jungle to dry, semi-arid subalpine. The river, too, changes its persona, from a meandering lowland stream to a mountain river, leaping down its steep rocky bed. The rocks of the mountains again become bare and twisted, pushed up, folded, buckled, and shattered.

We follow the same pattern as our journey over the ranges a few days ago, but in reverse. The jungle-clad escarpment, the sub-alpine valleys, an ascent through thick mist to a high alpine hinterland, and finally, a descent to the hot, parched plain. The landscape here is incredibly eroded and has a verticality that seeks to defy the imagination. Huge rivers of shingle descend from the shattered heights, forming vast fans of debris which are etched with fissures and runnels. Yet even the most vertiginous of slopes support conifers and other trees, whose roots have gained a toehold in the bare rock, and which now seem to peer down at the human activity passing below.

An ominous reminder of the dangers such rocky heights pose is the occasional concrete chute to carry rockslides across the road and down into the river.

TO BE CONTINUED…