We are awake early, around 7.30am. The night had been cool and pleasant, and we had slept well. There are several Westerners staying in the hotel, and I get talking to a gaunt, bearded Englishman called Mick, an ex-policeman who is riding a motorbike from England to Australia. He comes into our room, and we sit drinking tea and talking. It is good to speak English with an English-speaking person again. We discuss many things, mainly the state of the world and Africa. Mick has travelled quite extensively in Africa as well.

Out on the streets of Esfahan, the morning is cool and the air is fresh. We walk up the Maidan-e-Imam Khomeini, then left along to the main square. The sight that greets us as we emerge through the gateway into the square is stunning. Laid out before us in the bright sunshine is the massive rectangle of the Naqsh-é Jahan Square. At the far end of the square stands the exquisite Masjid-e-Imam Khomeini, formerly and more appropriately known as the Central Mosque. The entrance portal to this jewel of the Islamic world is one of the most beautiful examples of Persian Safavid architecture in Iran, and it stands out as a glorious reminder of what Persians can do when they aren’t constrained by the drab, uniform, Soviet-style of building that is common in Iran today.

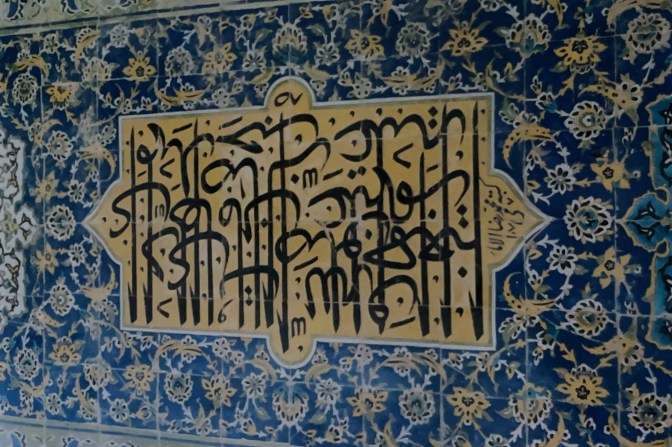

Entering the north-facing gate into the east-facing courtyard of the mosque, we walk through a series of vaulted corridors to emerge in front of the huge main cupola. The entire mosque is faced with delicate tilework in many different shades of blue. Flanking the main cupola stand two beautifully proportioned minarets, dark blue in the bright light. There are several quiet side courtyards with cool, shady trees growing in them, and we rest a while under one of these.

The mosque is just too much to take in at once, much less to try and describe later. We walk out into the square and buy some cold drinks from a couple of young salesmen. A selection of English speakers begins to annoy us, so we move on around the square. Most of it is unremarkable, shops selling what the book describes as “gimcrack souvenirs.” A maniac beats his head against a post, gibbering and frothing at the mouth. A group of kids sit watching him. The lunatic seems unaware of anything except whatever demons he is confronting in the post.

We complete a circuit of the square, passing the entrance of the bazaar. A man asks us in English if we are “with Encounter Overland.” We reply that we are not and that we do not want to see carpets. But he is persistant and I finally have to tell him to fuck off! ¹Encounter Overland…not a good sign.

The Palace of 40 Pillars today only has 20 pillars, as the pool whose reflection provides the other 20 pillars is empty. The palace is impressive in its size, however, but slightly tacky with its mirrored ceiling and murals. The murals graphically depict battles fought by the armies of former shahs and scenes of merriment and debauchery. When David St. Vincent visited, three of the murals were covered by screens, apparently because they depicted “un-Islamic activities.”

Today, only one of them is covered, but partly visible through a crack in one of the screens. It depicts a polo match, very un-Islamic. It is hard to see anything very human in the others, although two of them contain dancing women and people drinking. To a miserable mullah, I guess pictures of people having fun are un-Islamic.

Near the hotel, we buy a snack and get talking to a young Czech named Martin. He and I set off over to see the Masjid-e-Jame Mosque, a half-hour walk away. Linda goes back to the hotel. Close to the mosque, we take a shortcut down through the bazaar that leads diagonally towards the courtyard of the mosque. The bazaar is colourful and busy, a multitude of smells, stalls selling clothes, jewellery, spices, shoes. The ceiling is vaulted, and at the centre of each domed vault, a circular port lets light into the interior of the bazaar in bright, hazy shafts.

We emerge, blinking into the bright sunshine outside the mosque. Before us stands a huge wooden door set into a mud-brick wall. We enter the mosque through a corridor with vaulted iwans either side. No one asks for money. The Jame Masjid is less stunning than the Masjid-e-Imam, but still is a wonder to behold. To the left of the main central courtyard, the praying hall of the mosque has a richly decorated façade and stalactite mouldings. The main dome of the mosque is undecorated inside or out, and is over 800 years old.

Leading off on both sides are a series of vaulted cloisters, with dusty floors and shafts of light penetrating from the ceiling vents. There is barely anyone around, and the cloisters have a marvellously serene air to them. The artistry of their construction, from mud-bricks, adobe mortar and wood, are a tribute to the men who built them centuries ago and with rudimentary tools.

A few people are praying, both in the main part of the mosque and in a small prayer room at the western end of the mosque. We sit in the shade and watch the life of the mosque pass by, chuckling as a man pedals furiously to start a Solex scooter, then putters off down through the praying room. I giggle at the thought of someone riding a motorcycle around in Westminster Abbey.

After an hour or so, we walk back to the hotel, taking a detour through a part of the main bazaar. It is after 2 pm, so the shops are closed, their shutters down, their keepers asleep or at the mosques. A few semi-torpid shopkeepers doze amongst their wares, but the streets of the bazaar are empty of shoppers and quiet.

Back at the hotel, we too all retire for the afternoon. The hotel has attracted a good cross-section of travellers, and in the evening, Linda and I sit out in the small courtyard in front of our room and talk with Martin and two Japanese guys freshly arrived from Shiraz. The conversation is varied and typical: political situations, travellers’ information, and places visited. We all troop down for a meal at the Noshtbahad restaurant, then Martin and I catch buses down to the Se-o-se-Pol Bridge, where we sit and drink tea, surrounded by a horde of Esfahani families out enjoying the warm evening and the carnival atmosphere which prevails around the bridge.

We walk back to the hotel. It takes about an hour, but is very pleasant, strolling along the quiet riverbank, which has an almost European feel to it. People are picnicking on the lawns, a few are camping, rolled up in blankets on carpets laid out on the ground. The occasional couple canoodle in the deepest shadows. The lights of the bridge reflect in the flat waters of the river, and a lofty fountain, illuminated with green and orange, plays on the far bank. By the time we reach the hotel, it is late, and most of the town is asleep.

¹Encounter Overland was an English vehicle-based overland company that operated from 1968 until the early 2,000s. Whenever these truckloads of tourists were in town (any town in Africa, Asia or South America) prices would go up and local hawkers would become extremely pushy and hard to shake off.