The route from Lahore to Pindi lies along Sher Shar’s Grand Trunk Road, a two-lane highway lined with gum trees and factories. Beyond the grim belt of industry lies an Arcadian landscape of fields, lush and viridescent. Buffalo lie almost completely submerged in muddy pools like hippos basking in an African river. Abundant crops of rice stand ripening within paddy fields demarked by raised earth walls. Palm trees provide shade for people already taking breaks from the morning’s toil.

The journey is broken at a PTDC [the Pakistan Tourism Development Corporation] restaurant where we dine on chicken masala and hot roti. A large group of old men shuffle in, eat, and dpart in the time it takes to drink a Pepsi. Closer to Rawalpindi, the road crosses the rugged fault lines of the area known as the Main Mantle Thrust. Ragged pinnacles of red sandstone, remnants of 20 million year old sand stones eroded from the Himalayas, jut from the landscape like broken teeth of some fossilised prehistoric creature.

‘Pindi is hot and busy, and we take a taxi from the bus station to the Saddar Bazaar area. The Hotel Al Azam, in the very centre of the bazaar, provides us with simple, somewhat shabby rooms for ₹100 per room. In the evening, Blue, our Australian friend Joff, and I go out for a wander around the bazaar. I get a shave for ₹5 and Blue gets a haircut for ₹10.

Although peaceful, the hostel is squalid and without water. So next day we shift camp — after a hot sleepless night — to the Salvation Army hostel. Not, in fact, closed, merely being repainted. Our New Zealand friends Blue and Kerry are already there. Our only job for Monday is to go to the Post Office and send home our souvenirs of Iran. Linda is sick in the evening so stays at the hostel while a group of us go out to the mall to eat at a Chinese restaurant.

As usual, there is an eclectic bunch of people staying in the hostel. Our dining group is made-up of myself, Blue and Kerry, and two Brits, Fiona and Sam, who have spent eight months in India, and Mike, a hard case American with a deliciously sardonic wit. During the meal, we talk about Indian misspellings. Sam tells us about a menu that said “price is liable to change during meal.” Mike’s pork foo yung contains bacon.

Back at the hostel, after an agreement with the rickshaw wallah over the fare, Imran, our acquaintance from the border, turns up. Blue and I go for a drive with him and we arrange for him to show us around Lahore the next day.

Sloth is the by-word of life at the Salvo hostel. People stir around 8:00 AM, wander across to the bakery to buy something for breakfast, then relax in the knowledge of a day’s work well done. I lie on a charpoy out in the yard, reading until 11, when Imran arrives to take us sightseeing. Linda and Kerry are both feeling unwell so only Blue and I accompany him.

Our first stop is the magnificent Badshadi Mosque, built in the 7th century by the mean-spirited and orthodox final Great Emperor of the Mogul era, Aurangzeb.

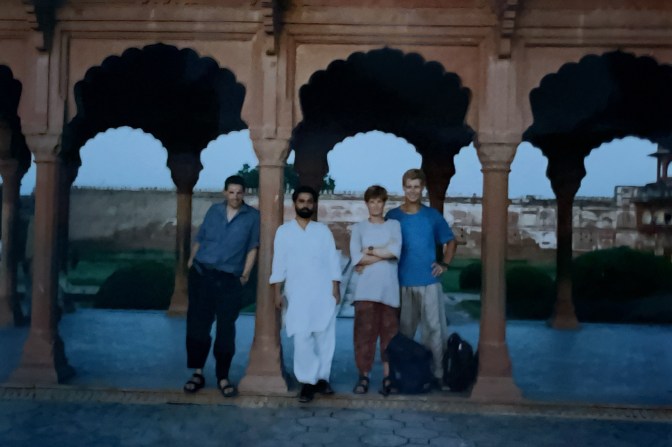

Leaving our shoes at the entrance, we stepped through the arched doorway into the huge courtyard, which is large enough to hold 60,000 worshippers. The fierce midday sun has baked the red paving stones to a degree which makes them unbearably hot to stand on. We follow a path of felt mats across to the right hand side of the courtyard, along which runs a raised, covered walkway. Wide porches look out to Iqbal Park with its Eiffel Tower-like monument, and Imran explains that the Ravi River once ran along under the wall of the mosque which is why there are no windows in the tower part of the wall.

We complete a circuit of the mosque, passing through the great prayer halls beneath the great domes. The minarets are closed to visitors because, Imran says, people were continually committing suicide from them, and occasionally screwing atop them. To the left of the mosque, stands the squat tomb of Maharaja Rajit Singh and Imran takes pains to inform us about the heinous acts of vandalism perpetrated by the Sikhs during his reign. To the right stands the simple tune of Mohammad Iqbal, Pakistan’s most loved and revered poet, guarded by two stone-faced soldiers.

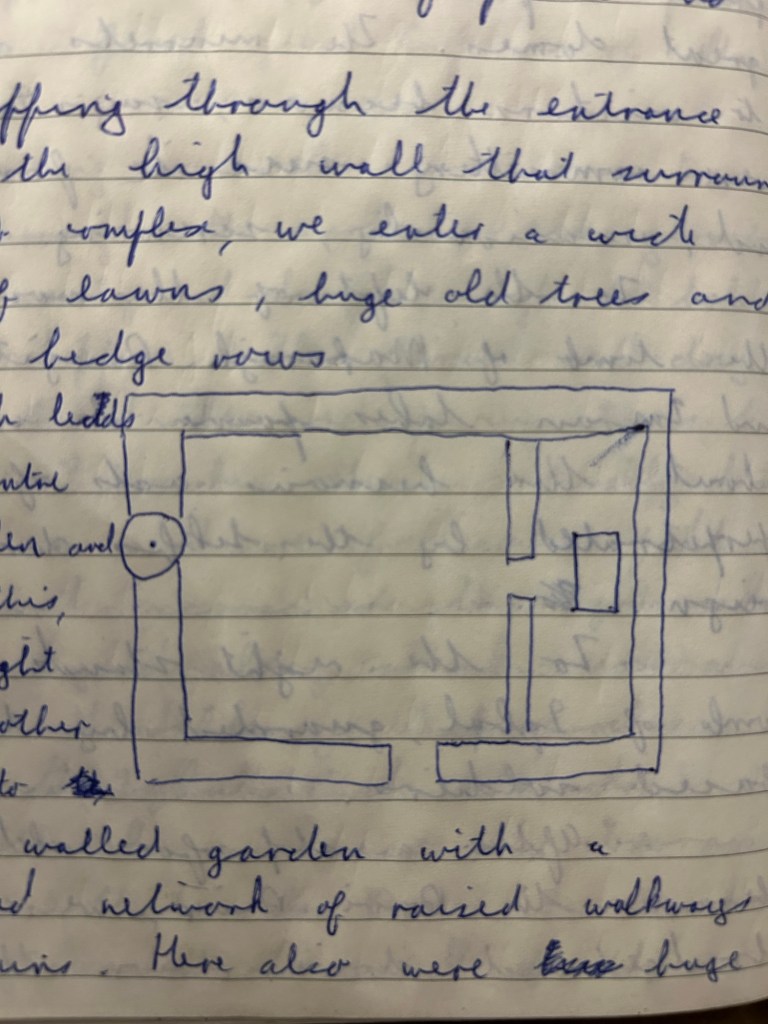

After a stop for cold drinks beside the Ravi River, we crossed the bridge and drive down through groves of palm trees, beneath which herds of buffalo take their rest, to the tomb of the mogul Emperor Jehangir. Set amid a shambolic mess of houses and fields, the tomb is a haven of peace and solitude. Stepping through the entrance gate in the high wall that surrounds the tomb complex, we enter a wide garden of lawns, huge old trees, and well-kept hedgerows. A path leads down to the centre of the garden and we follow this, turning right through another gateway into a second walled garden with a complicated network of raised walkways and fountains. Here also are huge old trees, mangoes, walnuts, cypress, beneath which a few fat buffalo sit chewing their cuds. The occasional person lies about in the shade, some of them gardeners perhaps, looking like nothing more than piles of dirty white rags.

The entrance to the tomb itself is ornately decorated with tilework. Leaving our shoes at the door, we step over the worn marble doorstep into the cool, dark passage that leads to the inner chamber, where stands the richly decorated sarcophagus of the emperor. Light enters the chamber through delicate marble lattices set into each end of the four short passengers at right angles to each other. Despite the jabbering of a self-important old man explaining about the tomb to a Pakistani couple, the place is very peaceful and still. The coffin, which is quite small, is intricately decorated with petra dura work of the same designs that graced the Taj Mahal. Shah Jahan was, of course, Jehangir’s son.

Inscribed on the side of the white marble sarcophagus are the 100 attributes of Allah written in beautiful Persian calligraphy. Overhead hangs a rather tacky brass candelabra, the only thing that detracts slightly from the overall beauty of Nur Jehan’s monument to her beloved husband. Her tomb, smaller and less ornate, lies across the railway line from that of Jahangir. The two were once part of the same complex, but the British, with typical colonial insensitivity, built the railway line between the two. Apparently, her tomb was plundered by the Sikhs for material to decorate the Golden Temple in Amritsar.

Driving out from the area around the tomb we pass through an idyllic landscape of palm trees and rough huts. Large herds of buffalo, kept for milking, take their ease in glutinous pools of mud. Back in the chaos of Lahore, Imran drives us into the Old City through one of its 14 gates. The streets of the Old City, normally bursting with life and commerce, are today virtually empty due to a national strike called by the opposition. Earlier on, as we drove down the Mall, we had passed a chanting crowd of men, closely followed by a knot of police armed with batons and wearing helmets and flak jackets. During the day, there were various disturbances throughout the city, including some gunfire.

Next, we visit the mosque of Wazir Khan. This small mosque is richly decorated with calligraphy painted on the walls rather than inlaid with tiles. Prayers are in progress and I take the opportunity to ask Imran to explain the Muslim procedure for praying. Firstly, with hands held beside the head, the worshipper absolves himself from the outside world. He then kneels and prays about the greatness and omnipotence of God and recites portions of the Quran. Repeating the prayer about the greatness of God, he presses his head to the ground. Finally, he greets the angels of good and bad that are perched on each shoulder. The process is repeated two to five times, depending on the time of day. I asked if there are circumstances in which a person may be excused from praying, for example, while being sick or imprisoned, but there are none.

Finally, we lunch at a sidewalk restaurant serving only one dish, cello, a tasty stew of chick peas, ghee and tamarind gravy, eaten hot with bread fresh from the tandoor, it is delicious. Following lunch, we’re dropped back at the hostel for a siesta.

Imran returns at 4:30. Blue and I are playing cricket with some kids on the lawn. The Salvation Army band is practising in the church hall, sounding like hell. Their rendition of Onward Christian Soldiers is particularly discordant. One of the army wives, herself a trumpet player, tells Linda and Kerry that has taken three years to get the band to this standard.

Imran takes us all out to the Shalimar Gardens. The sun is dipping towards the haze of the horizon like a huge yellow searchlight, casting long shadows across the gardens.

Set out in three tiers, the gardens are a model of order and geometric precision. The first tier, just inside the gate, contains two large lawns dotted with large trees. Down at centre runs a shallow pool containing the nozzles of several dozen fountains. People are reclining on the cool grass, talking, playing cards and a few are flying kites.

From outside, the roar of the city is still audible but diminishes as we walk towards the entrance to the second tier. This consists of a series of square tanks or pools surrounded by rose gardens. At each side stands a sandstone pavilion and concrete pathways cross the tanks. Each tank is nearly empty of water, and protruding from each are dozens of concrete pinnacles looking like egg clusters in the hold of the decrepit spaceship in the movie Alien. The water from the tanks runs down to the third tier through a marble enclosure, cubic in shape, its four sides recessed with hundreds of arched alcoves in each of which used to burn a candle. This would have been a lovely sight in its heyday, with its now disused fountains playing and the candles casting arched shadows through them. The 3rd and lowest tier consists of a similar arrangement to the first, with wide lawns, trees and pathways.

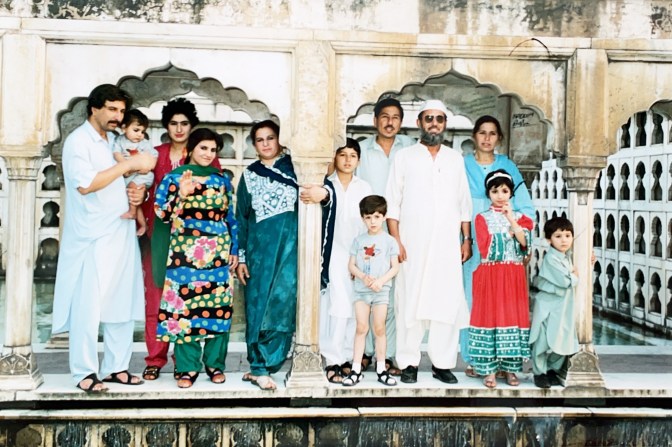

From the garden, Imran takes us to his house, a large old place with rambling gardens and a crowd of servants. We sit out in the backyard, drinking 7UP in the cool darkness as huge bats flap overhead and swarms of mosquitoes dive-bomb us. Imran has some business to attend to, so he sends us off with two of his servant boys to look around the large park, which backs onto his house.

The park is crowded with people out strolling, jogging, and picnicking. Lovers rendezvous for secret assignations and shadowy corners. Children screech and scream around the fountains. We are the centre of attraction. The centrepiece of the park is a rather over-the-top artificial waterfall hissing out of the ground with a huge torrent of water appearing as if by magic at the top and plummeting to the pool below. It reminds me of the waterfall at the head of the Te Moana Gorge, where Callum, Linda and I1 swam on that hot Friday afternoon at the beginning of the year. Beyond the waterfall, a series of fountains play out a complex pattern of yellow, blue, red and green.

Our loop of the park takes us an hour, ending up back at Imran’s house. He takes us for burgers at the Salt and Pepper Restaurant, then drops us back at the hostel. I sit up late talking with Mike the Yank and Sam the Pom.

1My former employer, Callum Mckerchar, Linda and I took a few hours off one hot summer afternoon to go for a swim at a waterfall in a river near the farm where we were working.