From the menu at the Limin Restaurant

WELCOME TO LIMIN RESTAURANT. WE WANT TO INTRODUCE YOU TO THE VARIETY OFSERVICES WE PROVIDE TO MAKE YOUR STAY IN KAS-GAR MORE PLEASANT AND CONVENIENT. FIRST OF ALL. WE FEEL YOU WILL FIND OUR FOOD VERY REASONABLY-PRICED AND DELICIOUS. AND BECAUSE OF OUR VARIED SURROUNDINGS, YOU CAN SOAK IN THE UNIQUE LOCAL CULTURE WHILE ENJOYING YOUR MEAL…

On the menu, the food which could be enjoyed while “soaking in local culture” includes:

HAMBUGER

FISH FLAVOURED WITH SLSICED PEPPER

SHREDED BEEF WITH SPING ONIONS

TYPICAL GERMAN BRAT

FRIED POTATO

COLD BEACURD

COME SOME OF BEANCURD WITH VEGETABALL SUP.

It was a cool place to hang out, and apart from a few forays about town on bikes, we spent most of our time there. We made an eclectic bunch of new friends during the long evenings of drinking beer and eating. Rhys, a languid, soft-spoken photographer from Melbourne, has a way of drawing his words out into a drawl (“Yeeeaaaahhh.”) Terry, an American from Chattanooga, Tennessee, and his friend Mike from New York City. They are two cyclists we had met on the road to Tashkurgan a few days before. Terry and I hit it off well, discovering a mutual sense of humour and common taste in music. While at college, he had seen Steve Forbert play a couple of times in Jackson, Mississippi. In his laconic accent, he told me: “Yeah, little Stevie. He comes from Meridian, Mississippi. Last time I saw him, he was a fat old man with an afro that didn’t fit. He tried to make a comeback [with the album Streets of This Town] a few years ago, but hell, he was still living with his mother.

On our first morning in Kashgar, we rang home from the post office and got Joe and Helen to ring us back. We both talked for ten minutes each, me to Joe and Linda to Helen. The days passed slowly and pleasantly, getting up late and retiring late after stuffing ourselves with the good food at the Limon Restaurant. But on Saturday, a perceptible change in the town’s population began to take place, as scores of people began to arrive for the Sunday market.

On every street, people carrying merchandise or driving laden donkey carts hurried by. I saw some trucks carrying prisoners, their heads hung in humiliation, being driven around the town. The atmosphere was one of great expectation as Sunday market day approached. On the Saturday afternoon, as Blue, Terry, Mike, and I sat drinking beer and talking, a drunk began annoying the owner of the restaurant. An old man, who we presumed to be the father of the owner, stood up to the man, a sly-looking Uyghur, with remarkable skill and courage, until he went away.

On Sunday morning we’re all up early and arrange for a motorcycle taxi to take seven of us to the market for ¥15. It is a cool, smoky morning, and as we bump along the streets of Kashgar, we become part of a tide of people, all heading for the market. Up to 100,000 people convene every Sunday for the Kashgar Sunday Market, making it probably the largest open-air market in the world.

Splitting up from the others, Linda and I lost ourselves among the narrow streets and byways of the market. Walking down through an alley, we passed a group of food stalls, where men were preparing dumplings and noodles for the crowds. Vats of sheep’s head soup bubbled over fires, and hordes of wasps hovered over stalls selling lumps of crystallised sugar.

We follow a man leading two fat steers and find our way to the enclosure where all the livestock is sold and traded. Groups of bearded men with leathery skin, wrinkled faces and beards, dressed in blue pants, long coats, and knee boots, haggled and shouted over prices. Sheep and goats were tied up in lines, some of them large and fat, others thin and pathetic. Cattle were tethered to posts dug into the ground, and calves were tethered to carts upon which was placed some fodder for them to eat. There was what you might call a “large yarding” of donkeys, some braying, some with huge erections. Six Bactrian camels were on offer, but seemed to attract little attention.

Around the perimeter of the compound, vats bubbled and steamed with horrid-looking concoctions of offal and meat, and craggy men sat on the ground behind, tucking into bowls of noodles and…things. Outside, stalls sell halters, reins, bridles, and the paraphernalia of farmers. There are yokes, carts, knives, and steelware. Chests of beaten brass, baby’s cradles, lumber, and tanned leather.

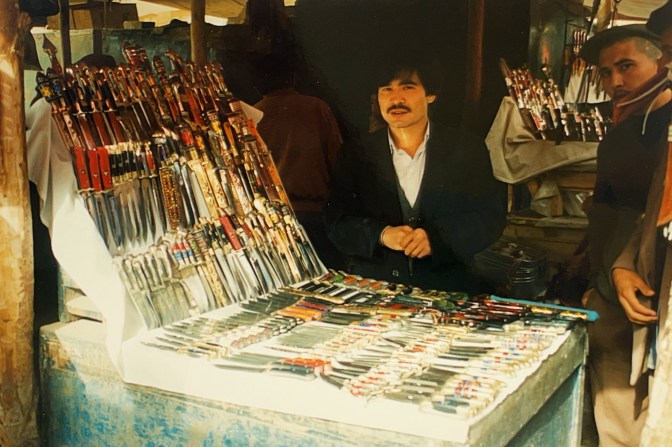

There are many white faces mixed in with the brown ones. Many of the tourists here are whisked in for the Sunday market by plane, then whisked out again. The previous night we had witnessed the arrival of one such group to the Seman Hotel. They were greeted by applause from the hotel staff lined up outside. The presence of a large number of tourists, among which we, however reluctantly, had to be numbered, meant that prices were high and virtually non-negotiable. In the knife bazaar, I had to haggle hard to get two small knives for ¥30. As we haggled, the merchant greedily eyed fat, old-aged European tourists strolling by with their wealth displayed in dangling cameras and gold jewellery.

After a meal of dumplings at a stall, we return to the livestock compound, which is now overflowing with buyers, sellers, and their stock. A clear space down the middle of the compound is a track where prospective buyers ride horses and donkeys to test them out. Knots of men haggle furiously, and often violently, over different set lots of animals.

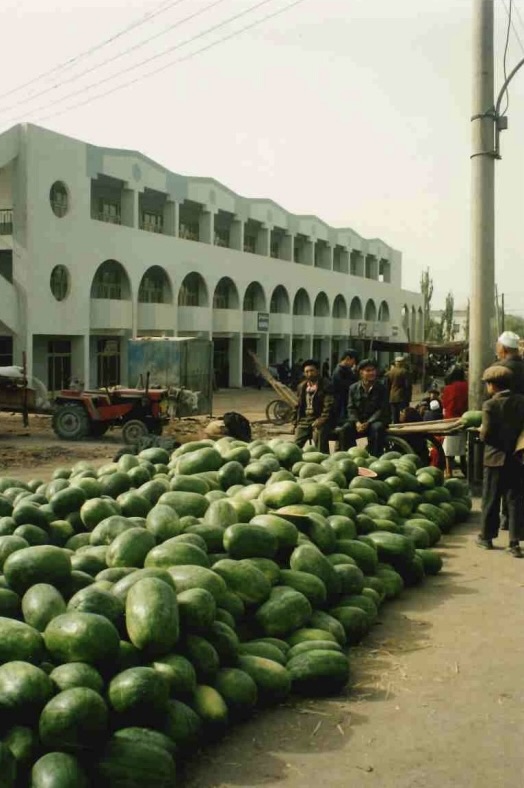

There is much jostling, shouting, and gesticulating. The grabbing of a hand and rubbing it in the dirt appears to signify a clinched deal. Buyers pay with notes drawn from huge wads produced from inside coats. Sellers wait for buyers while munching slices of watermelon cut with wicked-looking knives. Tire kickers stand in groups, talking over prices and quality. The entire scene is reminiscent of any stock sale anywhere in the world. There still seems to be no takers for the six camels.

At midday, we wander out of the market along a street lined with stacks of tin basins and containers. Dotted amongst these, apothecaries sell potions and cures, and a few dentists have their surgeries in dark rooms behind. We take a cycle taxi back to the hotel and crash out for the rest of the day. In the evening, we all get together for a last meal before going our separate ways.

At 5:30AM on Monday morning, the four of us, along with Rhys, take a taxi to the bus station. It is dark and cold, but there are many people already out. A large group of women and men march to work along a street. People are sweeping the streets with wicker brooms, each person enveloped in a cloud of dust which is illuminated by the headlights of passing cars. Clustered around one of the main roundabouts, several hundred donkey carts laden with cabbages stand as if asleep. The entire roundabout is clogged with them, obviously waiting for something, but what?

Mao’s statue is lit by some fuzzy searchlights. In the cold light, he looks as if he is changing a lightbulb. This is perhaps a good metaphor to apply to the man, as he tampered with the wiring of China for many decades and only succeeded in blowing fuses. Now he is reduced to changing an invisible lightbulb on a cold industrial street in Central Asia.

At the bus station, we wait with the crowd outside until 6AM when the doors are opened and we can all file in. Out on the compound, we board the sleeping bus which is to be our home for the next 36 hours. It consists of three rows of short, narrow bunks, one row down each side and one down the middle. I take one in the middle row and Linda one on the outside. From the top bunk there is nothing to see, and apart from a goods train pulling 32 wagons and three desert noodle stalls, I see nothing of the Taklamakan Desert along the edge of which the road runs.

I pass the trip listening to my Walkman and reading Jung Chang’’s interesting, although long-winded, account of life in China between the 1920s and the 1970s called Wild Swans. We arrive in Ürümqi at 3PM local (Beijing) time on Tuesday, October 11.