Commotion. Again awakened early by shouting, banging doors, dreadful coughing and spitting sounds, the bus station…the picture becomes obvious. Down in the restaurant, over a breakfast of eggs, toast, coffee, and orange drink, we chat to an English guy whom we invited to sit with us. One of the problems with a hotel like the Traffic is that everyone is closeted in separate rooms on different floors, and this precludes making dorm- and shower-block acquaintances. Also, many of the people here seem to be in groups of four or more, and this makes it hard for people alone or in twos to meet new people.

So when the Englishman begins looking around for somewhere to sit, I invited him over to our table. He turned out to be quite a nice chap indeed. Older than us, maybe 40ish, originally from York, but lately from Liverpool, and well-travelled. We yarn for an hour or so over breakfast, discussing the politics of Iran, the pros and cons of foreigner pricing, and the state of Deng’s health. He is reputed by some sources to be in a coma.

After breakfast, Linda and I set off to trek to the zoo, which initially involves a visit to the Friendship Store to try and change money. We opt for a ride in a tri-shaw for the 1km trip, for which the little man, obviously a true capitalist, one of Chengdu’s many, tries to charge us twice the price we had agreed on, which we, of course, refuse to pay.

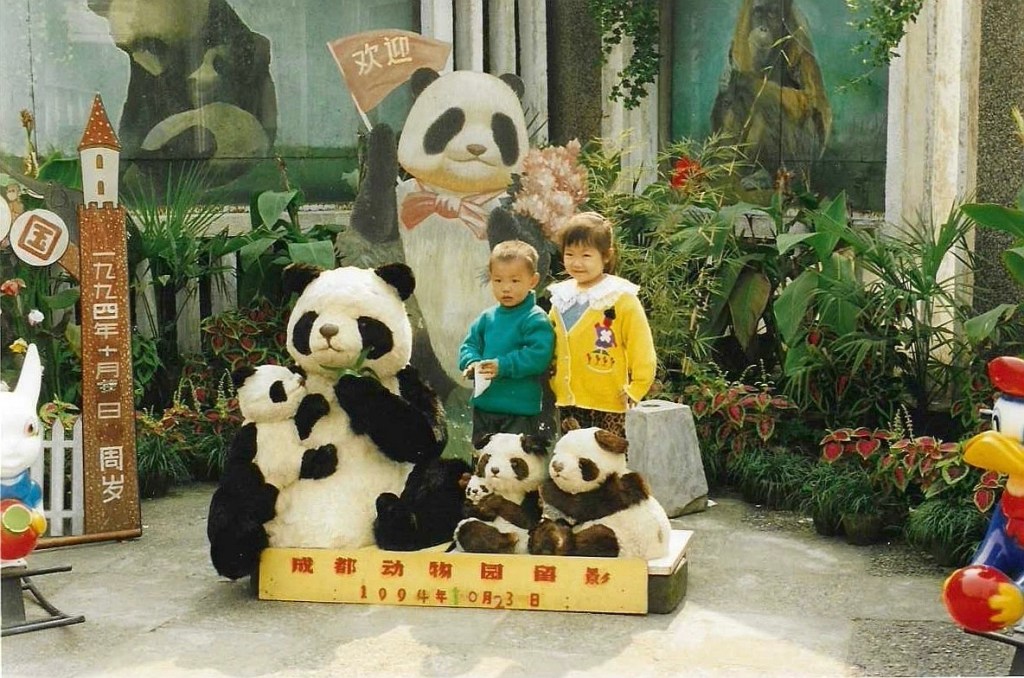

The bank is closed, so we set off out to the zoo. Our aim is to see the giant pandas that they have there, and this we succeed in doing. The pandas, great fuzzy creatures with big sad eyes, are healthy and well fed. But the conditions in which they are kept is very saddening. Concrete chambers, steel bars, an area of long grass with a couple of pipe ladders. There is nothing to stimulate the bears, and no effort is made to recreate their natural environment.

The bears lie about lethargically, while hordes of Chinese onlookers screech at them, vainly trying to elicit a response. After a very short time I begin to feel the sadness of the pandas, and we leave. The zoo feels like a concentration camp for all of the animals and birds housed there, and it is long while before the images of those great sad intelligent eyes left me.

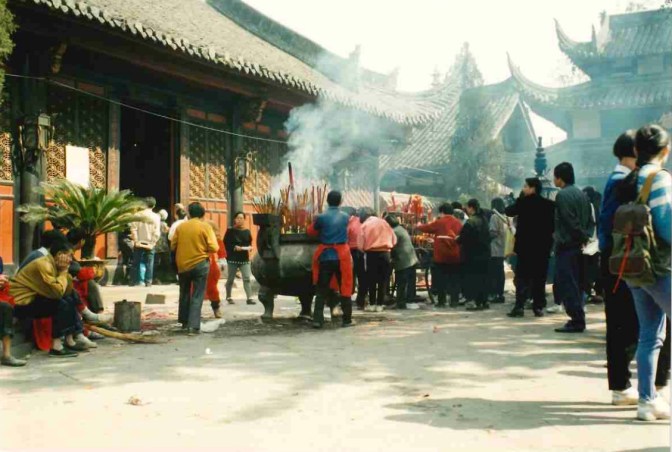

We get lost finding our way back into the centre of the city. Buses suddenly terminate, route numbers suddenly change along with street names. But around midday we find our way to the alley leading down to the Wenshu Monastery. The alley is a riot of colour. Small stalls sell paraphernalia for the appeasement of the Buddha. There are joss sticks in sizes ranging from knitting needle size up to baseball bat size. Stacks of imitation money, incense burners, garish posters of the Buddha, paper wreaths of pink and red and orange, and a dense press of people and bicycles.

We run the gauntlet of bent limbs and decaying flesh held outstretched by the beggars clustered around the ticket stall, then walk into the temple compound. The temple itself is centred around a square courtyard of grey flagstones and consists of three separate pagodas containing effigies of the Buddha. Outside each pagoda, people pray to the Buddha and light bundles of incense, which they place in large sand-filled stands. Attendants constantly gather up the incense sticks and make room for more. A large brass burner outside each temple receives offerings of money and rosettes, and stands hold fat red candles upon which incense sticks are lit.

Next to the temple, and accessed through it, a small park is alive with groups of people playing cards, telling stories, and relaxing. We wander slowly along the twisting pathways beneath groves of trees, pausing occasionally to watch games of checkers or mahjong. There are some wonderful faces in the park. Old, lined faces. Crooked, toothless smiles. Old people who must have seen so many changes, many of them unfathomable, in their lifetimes.

The park’s teahouse is crowded with Sunday groups, families, friends, businessmen talking into cell phones, children screeching and shouting. At the gateway back out onto the street, we sit for a while watching people. The young ones are very different when seen in comparison with their elders. Young men dress snappily in approximations of stylish Western suits. The young woman, many of whom are very attractive, strive to emulate the fashion idols of the West: platform shoes, long body-hugging dresses, and extravagant make-up. The contrast between them and the older people, clad in their ubiquitous blue suits, is obvious and important. No more cultural revolutions for the China of today. Western culture and capitalist values are here to stay.

From the temple we take a bus up Renmin Bailu to the river where we have a snack at a riverside cafe. Across the river, the tea houses are crowded and it is to one of these that we repair after a nap at the hotel. The river is a foetid grey colour in the late afternoon sun and the air is a thick pall of blue smoke. Downstream, hidden from view, a factory pours pink smoke into the atmosphere and it drifts up across the city. There appears to be no controls on the emissions of factories nor any attempt to halt the appalling air pollution of the city. And in the river, the languidly drifting corpses of animals are the cleanest things. Peter Bruegel would have found much to inspire him.

In the evening we dine at the “world famous” Flower Garden Restaurant. Mozart wafts across the river on the heavy breeze and candles cast muted shadows beneath the trees overhanging the river. The glow of Lonely Planet’s spotlight has somewhat gone to the heads of the management however. The food, when we get it is bland and uninteresting, and the staff are arrogant and smarmy.